“Why have I not seen any sea level rise in 40 years?”

Salt Whistle Bay (CC Stefan Schäfer, Lich)

Many years ago, while evaluating a location for some investors, I met a Canadian attorney on this tiny island in the Caribbean. To be specific, it’s Mayreau, the smallest island in the Grenadines. “Jim”, the attorney has been following my work on rising sea level, with great interest. Recently he noted that he has not witnessed sea level rise on Mayreau in the four decades plus since we first visited and asked if I had an explanation. It’s a common question and worth explaining as it applies to ocean fronting locations worldwide.

I should mention that sea level can vary considerably from one location to another, but that will be the subject of a future blog post. For this explanation, let’s look at global average sea level, more accurately Global Mean Sea Level “GMSL”.

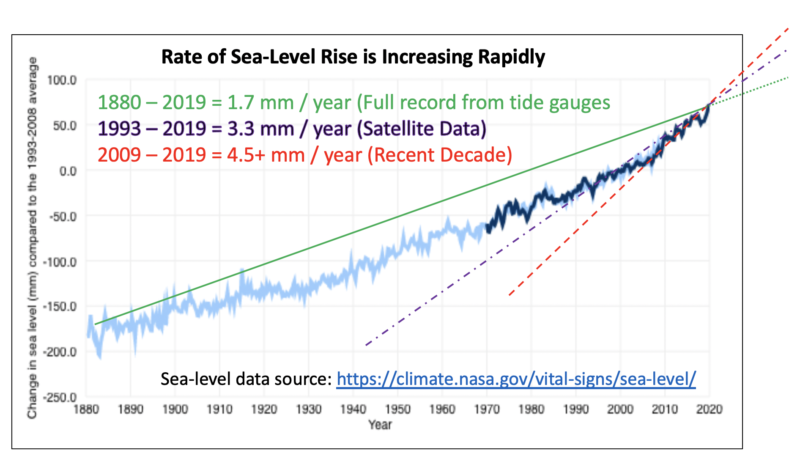

Over the last one and a half centuries of measurement, global average sea level rise (SLR) has been about 1.7 mm a year (6/100-ths of an inch), rather trivial. Like a drip filling a bucket, the effect happens over time; it’s the accumulation. An even bigger effect is the acceleration of the rate. Since 1992 when more precise SL measurements started via satellites, the rate has been 3.3 mm average per year — double the average of the last century. In the last decade it has been 4.51 mm, a further 50% increase. This graph may help to see the increasing slope of the trend line over the last 140 years since tide gauge records began.

Where is this headed is the obvious question. It appears the “doubling time” is now less than 15 years. The accelerating rate could even become exponential. To understand where this could lead, see a previous post illustrating the magic of doubling times.

Back to the observation at Salt Whistle Bay — or any other beach for that matter… Even taking an annual rise of 3.5 mm over 45 years, that is about 16 cm (6 inches), a modest amount when spread over that long time period. With acceleration of the melting ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland, we could have double that rise by mid-century.

Higher base sea level also means that short-term flooding will be even worse, even with just six inches. Given the confluence of waves, varying tide states – daily, lunar monthly, and the 18.6 year cycle — and such things as changing barometric pressure, it is very hard to discern that rise by observation, with the naked eye.

In addition to the water height change, there are often larger issues of erosion, or deposition, the normal coastal processes whereby sand is taken from one beach and deposited elsewhere. That too can get confused with changing water level. In a particular place there could also be some land subsidence or uplift, adding to or reducing sea level. Even a comparative photograph would need to be taken at a similar point in the tide cycle to show change.

Rather than judge by our eyes or memories going back many decades we are better off looking at the facts through some consistent, objective measuring system. Globally, the water is rising and accelerating.