Retreat, Buyouts, and “Moral Hazard”

The U.S. Government is largely silent about “retreat” from the coastline – or at least does not use that word. Retreat has powerful connotations, particularly for property owners. It implies surrender. It carries great economic and political sensitivity. For many coastal communities it poses an existential threat. Nonetheless, managed retreat is increasingly a topic of conversation, as sea level rises, pushing the high water mark ever higher, even in good weather. The worldwide policy problems posed by the need to relocate tens of millions is one the world has never had to confront.

If the topic of retreat seems familiar, you may be recalling my blog post two weeks ago, “The 4 Realities of Retreat: The Florida Keys as Example”. The prior week I had written about the new free Flood Factor vulnerability assessment tool by First Street Foundation. Their analysis said that 14.6 million U.S. homes were at risk of flooding, 36% higher than the Federal government’s figure. Then last week, two different sources explicitly featured and focused on retreat.

- Georgetown Law School’s Climate Center conducted a webinar on their new Managed Retreat Toolkit, specifically created to help communities consider options to deal with challenge caused by rising sea level. Though it did not rise to mainstream media attention, I was quite surprised that over four hundred people were on the webinar about its release.

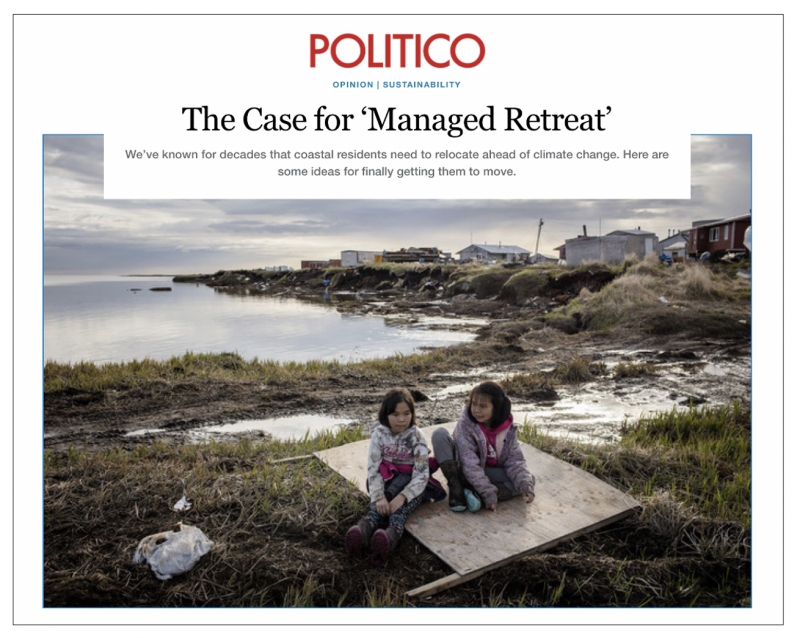

- POLITICO, the highly respected political news and analysis website, featured the story and image shown above, boldly headlining Managed Retreat. It’s excellent and worth the read. Right in the lead paragraph they refer to estimates of hundreds of thousands of homes being vulnerable to regular tidal flooding by mid-century, with a value of $117.5 billion. Then they note that it’s likely an underestimate (which I would underscore). The OpEd observes: “political leaders have not even begun a conversation or started to develop a national strategy for the massive dislocation that is inevitable and already on the horizon.”

“Buyouts” are becoming the preferred way to effect retreat inland as sea level continues to rise and accelerates. Generally done case-by-case, Federal and state governments purchase homes or actually move families to a new community. Buyout programs have evolved from dealing with repeat flooding on flood plains to responding to extreme storms like Sandy and Katrina and severe coastal erosion. In recent years the problem of higher routine water level at “king tides” is recognized as the larger issue that will scale up retreat.

According to the Politico article, in the last three decades, 43,000 voluntary buyouts have been done in nearly all U.S. states and territories. In some of the small villages in Alaska and Louisiana the cost approaches a million dollars per household, when the Federal government takes responsibility and handles everything to build a new village and move everyone. Limited programs to simply pay targeted homeowners a fair assessment of their home’s value can be far cheaper. That’s the path being used in New Jersey for the Blue Estates Program, featured in the Managed Retreat Toolkit and generally praised. From a simple perspective of using economic incentives and leaving the actual decision to the property owner, buyout programs have a lot of appeal.

It needs to be noted however that from Staten Island, New York to Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana not everyone accepts buyouts. By some estimates, up to a third of residents hold out. In some cases it’s a deep attachment to place, perhaps a stubbornness to “stand one’s ground”; in some there is suggestion of waiting for a better buyout offer. But in the face of inexorable rising sea, the problems mainly magnify with holdouts. With fewer residents, it becomes even more costly and challenging for local government to provide basic and emergency support and services.

But there is another problem with buyouts and relocation programs that needs to be considered. What is the precedent being established? Where is this headed? How does it scale? Is the concept that “the government” is responsible when people build in areas that have high flood risk making the problem worse? For example, in the United States, a person buying a home in a vulnerable coastal area may have three possible programs that transfer their risk to the public. First is the highly subsidized National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) which over time has come to reward owners of repeat flood properties. Second is the expectation that FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency will come to the rescue in the event of a catastrophic loss. Third is the expectation that they can wait for a buyout offer at “full” value.

While there are good justifications for each program, it is hard to escape the fact that without those three safety nets, that few people would build or buy homes vulnerable to flooding and destruction in low-lying coastal zones. To be clear I am not against “safety nets” and emergency assistance. But inadvertently these programs reduce the cost and risk of developing in high-risk areas, which fosters more development in those areas. Presumably if the only flood insurance was available from commercial companies with competitive premiums, the insurance cost would reasonably reflect the risk and be much more expensive. It would be a disincentive.

In economics, moral hazard is a centuries-old concept describing when someone has an incentive to increase their risk exposure because the true cost of their risk is shifted to others. From my view, that describes our situation with coastal flood risk.

At this point, there’s no easy answer to implementing smart policy. But the time has arrived to consider where things are headed, to look over the horizon. The coastal flooding problem is already getting noticeably worse with each decade. Though it is obviously politically appealing to think that “the government” – any government – will indemnify us and take on unlimited risk and expense, that is not sustainable. As we see with all manner of poorly considered public policies that subsidize irresponsible behavior, they lead to bigger problems. Costs escalate, leading to fiscal crisis, leaving things worse for the next generation. Good policies need to incentivize smart, sustainable, scalable behavior. People who choose to build in a high risk zone should be bearing the cost, not shifting it to the general public.

The present-day problem of increased flooding is just the tip of the iceberg. The problem is not just a few vulnerable places like Miami, New Orleans, Jakarta, Venice and Shanghai. Ten thousand coastal communities, from Charleston to Seattle, from Copenhagen to Calcutta, cities and rural communities alike, need to confront the new reality. The sea is rising; the pace is quickening. In some cases, elevation may be a solution, at least for a while. In other cases, putting things on floats or making them movable may work. But generally we will be moving to higher ground.* Some may pursue the knee-jerk response and move to the mountains, but the world cannot abandon the coasts. Ocean access is essential for a myriad of reasons and will be maintained, one way or another. In a world with a sea that rises for centuries, those that figure out how to adapt and function will not only survive, but will thrive.

* I should note that “Moving to Higher Ground: Rising Sea Level and the Path Forward” is the title of my forthcoming book. Look for a blog post in September or October with details and a special offer.