Radical Scheme to Stop Sea Level Rise ?

The Atlantic Magazine ran a feature a few days ago that is causing a buzz. “A Radical New Scheme to Prevent Catastrophic Sea-Level Rise.” It suggests that we might slow rising sea level by slowing the collapse of some gigantic marine glaciers in Antarctica. It is a bold claim that needs to be understood in terms of its practicality.

Good Academic Paper; Unrealistic Solution

Though it had some good information, the overall impression was misleading for the public. Given the enormous risk of rising sea level, I consider it a truly dangerous distraction. It described a graduate school paper by Michael Wolovick at Princeton, with a creative idea, appropriate within academia, where students are encouraged to think theoretically to bring new ideas to bear. But a careful reading of this proposal, does not suggest that anyone believes this particular idea is realistic. Such ideas need to be thoroughly “vetted” before put in front of the public as realistic. The title and a casual read clearly says that this is a possible way to prevent greatly higher sea level.

To understand the gross improbability of the headline, one needs to grasp the scale of the major glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland. Having led a number of fact-finding trips to both places I can attest that the size is hard to comprehend until you see it. To help, recall the first time you stood at the beach, and looked at the scale of the sea. That’s what the ice sheets look like first hand – vast, even seeming endless.

Greenland and Antarctica are each covered by a vast ice sheet a few miles thick, resulting from compacted snowfall over millions of years. Glaciers are rivers of ice, grinding along at a mile or so per year, taking the path of least resistance as gravity takes them to their final destination, the ocean. Glaciers may well be the most powerful, intense physical force on Earth.

They can be ten miles wide, a hundred miles long, and two miles high (3 km). No man-made structure has ever altered the course of a glacier. Glaciers essentially drain the ice sheet into the sea. When they leave the land, large pieces break off – called “calving” – and enter the sea as new icebergs, which do add to sea level, just as adding an ice cube to a glass. Also the meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets on land can run to the sea, sometimes as rivers of raging water. That too adds to sea level, just as pouring more water in the glass.

Wolovick’s Radical Scheme

So what is the radical scheme described in this article. Wolovick proposes building small islands of sand or gravel in the ocean, just in front of the largest glaciers where they meet the sea. These marine glaciers are special because they partly go underwater, essentially in a valley, exposing their underside to melting by the ocean, which has a lot more heat content than the atmosphere above. As a result the underwater melting happens much faster. His idea is that a man-made “sill” could block the flow of the warmer water to erode the glaciers, like a barrier island. (BTW, ‘warmer water’ here is a relative term, just a degree or two above freezing.) The theory is that slowing that underwater melting could significantly reduce the glacier melting, or even collapsing. Due to some peculiar dynamics, many of these glaciers have the potential to calve rapidly like a falling line of dominoes. It has now been shown that can happen, but no one knows the critical point that will trigger it.

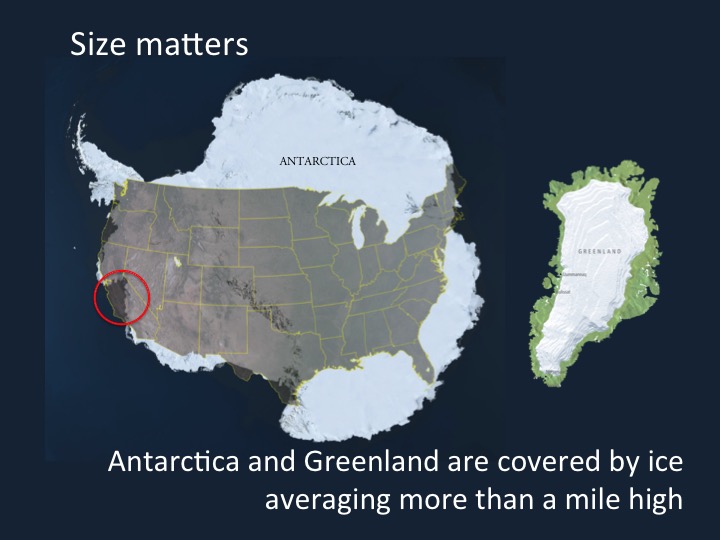

As illustrated here for scale, Greenland is about the size of the eastern United States. Antarctica is about twice the size of the continental U.S. In particular he focuses on the six Pine Island Glaciers in West Antarctica, which terminate in the red circled area on the map above. Just those six glaciers contain about ten feet (three meters) of global sea level rise.

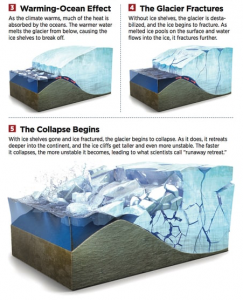

The largest of the six is Thwaites Glacier. Jeff Goodell did a superb description of Thwaites in a Rolling Stone article last year, “The Doomsday Glacier” with some good illustrations of glacial collapse, excerpted at right.

Back to The Atlantic article and Wolovick’s thesis. It is fine for an academic paper. In fact, we need to think “outside the box” and really should consider anything in the face of the looming catastrophe of rising sea level. Deciding what schemes are realistic, or at least worthy to place big bets upon is essential however. So here are my problems with this ‘radical scheme to prevent catastrophic sea level rise‘:

- The area that would need to be blocked from ‘warmer ocean currents’ is Pine Island Bay, circled in red on the map. Conveniently you can see from the overlay that this is roughly the span from Los Angeles to San Francisco. The water depth in Pine Island Bay is about two thousand feet. Constructing those barrier islands would be the largest civil engineering project ever undertaken.

- Recall that this is the harshest environment on the planet. Winter conditions in Antarctica are beyond brutal. Constructing something underwater, just offshore that would be durable given all the forces of ice in the area seems really dubious. (Still I am sure many engineers and contractors would scramble to get a piece of that project.)

- While it is way too premature to consider the cost, I think it’s fair to guess it would be in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

- Even if the series of barrier islands were built, the powerful swirling currents of the Southern Ocean may well get around them, either surging over the top, or cutting new channels in the seafloor, as happens regularly with barrier islands and sandbars.

- If the barrier islands did work, they might have the opposite effect than intended. By stopping the ocean currents from getting in underneath the glaciers, the water that is trapped there might get even warmer, accelerating the melting.

- In 2016-2017 the Pine Island glaciers were exhibiting other forces of destruction apart from the melting underwater by ocean currents, e.g. ponding water on top of the glacier that causes fracturing as depicted in the item #4 in the little graphic above from Rolling Stone. So even if we did construct these barrier islands, they do not really solve the problem. At best they might buy some time.

- As Antarctica gets into thawing mode, there are already other ominous places on the continent. Near where Florida points on the overlay maps above, there is a new concern about Totten Glacier, similar to Thwaites, but much larger, holding more than ten feet of global sea level rise by itself. We would have to ask, how many of these artificial barrier islands are we going to try to build around this colossal continent, in the hopes they work, while the glaciers melt at a quickening pace.

- In addition to the specific issues above, the biggest risk is to hold out false promise and distract us from realistic paths to prepare for rising sea level.

To quote the late Robert Wiegel, a National Academy of Engineering professor at UC Berkeley, and highly respected coastal engineer:

“For every complicated problem there is always a simple answer. And it’s always wrong.”

3 Options

My greatest problem with this concept being described as a solution is even more basic. Let’s assume for a thought exercise that “the world” might agree to try to this concept. To make this clearer, let’s say we hypothetically allocated 500 billion dollars for such a program in a desperate attempt to slow these mega glaciers that will cause more than twenty feet of sea level rise sooner or later. Would those resources be best used for that?

Or would it be more responsible to use that amount of money and resources to begin the coastal adaptation to raise, relocate, rebuild or make resilient the ten thousand or so communities around the world that will be submerged? Or even to put more resources into reducing the rate of warming from greenhouse gases, which is the driving force that is accelerating the melting in Antarctica. One might say, let’s do all of the above. But of course any money on ‘sketchy schemes’ is money not available to be invested in communities from Miami to the Maldives, or Copenhagen to Calcutta — just to cite a few places that could well justify a spare hundred billion for sea level adaptation. At the risk of oversimplifying we have three options:

- Start the ADAPTATION to higher sea level that is essential in a warmer world. Even if we achieve the goals of the Paris 2015 Climate Agreement (which is rather doubtful) we are still accepting double the current warming. Based on the last time the Earth was that warm, 120,000 years ago, sea level will eventually be twenty feet (7 meters) above present.

- Work as aggressively as possible to slow the warming (often called “mitigation”) by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and exploring ways to even remove the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Evaluate any possible efforts to slow the melting ice and rising sea level, the “long shot” solutions like the focus of this article in The Atlantic.

We should look at all three. We must pursue the first and second simultaneously to prepare for the sea level rise that is now unstoppable and to make every effort to slow the warming as soon as possible. And I agree we should keep looking for a smart, practical, realistic number three, worthy of a big bet, the so-called “hail Mary” pass. But any such risky or very expensive solution need to be rigorously evaluated since they have two costs: a) the actual cost to attempt it, which in this case is substantial, and b) the cost in time, delay and distraction that it could cause to solid efforts to adapt to much higher sea level.

Our new nonprofit, the International Sea Level Institute will work on all three, though the primary focus is Intelligent Adaptation. www.sealevelinstitute.org Our mission is to help the world Understand, Plan, and Adapt to rising sea level as a primary contributor to long term flooding.

We can adapt to higher sea level. In fact, we have no choice. The sooner we invest in the future, the better for us, and for future generations. Let’s be realistic. A lot is at stake.