Methane is a Major Danger — and misunderstood

Methane is in the news. It’s a big deal in terms of climate change, but mostly misunderstood. It’s important to set a couple of things straight.

Natural gas is essentially methane. Scientifically it is CH4, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Today it is in the news because the US EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) has proposed a new Methane Challenge Program to reduce methane emissions, particularly from the oil and gas sector – which is pushing back as would be expected. There is a lot of misunderstanding about methane, but make no mistake: Methane is a Major Danger.

When I get the question ‘What keeps me up at night’ at strategic planning or national security events, a large release of methane is one of the two things I cite. (The other is the catastrophic collapse of certain glaciers in Antarctica.)

Here are the basics:

Greenhouse Gases (GHG) are those chemicals that have high thermal insulating properties, like a sheet of glass in a greenhouse.

Sunlight comes in as radiant energy, hits an object and is converted to heat energy which is then trapped by the glass in the greenhouse, or the GHG in the upper atmosphere. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a big GHG and it is now at 400 PPM (parts per million), 40% higher than in about ten million years. That is the primary factor that has caused the planet to warm about a degree and a half F (nearly one degree C) over the last century. As I explained in High Tide On Main Street, that is what is melting the ice, which will eventually raise sea level tens of feet — but hopefuly not this century. Higher sea level is already amplifying the effects of storms and extreme high tides. Though rising sea level is no longer stoppable, we can slow it by slowing the increase of GHG, which will ultimately slow the warming — and must try to do so as urgently as possible.

Methane comes out of the ground (or animals) hundreds of times stronger than carbon dioxide in terms of effectiveness as insulation — the greenhouse effect. But it quickly breaks down in the atmosphere with an estimated ‘life’ of 12 years. When the curve of decline (like a radioactive half-life) is calculated, the strength of methane is 86 times more potent over the span of the first twenty years compared to carbon dioxide, and an estimated 34 times more potent over the course of a full century. (Note: there are a lot of outdated references to it being 25-30 times more potent but the figures I cite are above from IPCC-AR5 WG1, Table 8.7, the 2013 authoritative reference.)

Even though methane only lasts for about a dozen years, it eventually evolves chemically in the atmosphere to beome carbon dioxide, which is stable for thousands of years. Our concern is thus a double one for methane. As it is being put in the atmosphere in greater and greater quantity — and apparently many times greater than previously believed — it will add to the warming with 86 times greater efficiency in just two decades, than the same quantity of CO2. The period of a couple of decades is relevant as greatly elevated temperatures in the polar regions will affect the melting of glaciers in far less than a century. (The increased trapped heat is the main cause of higher sea level, now largely irreversible.)

There are several different sources of methane:

- Agriculture, particularly from cows

- Escaped methane from “Fracking” as well as the transport and handling of natural gas – this has been rapidly increasing due to the boom in natural gas production and use in the US. (Note: A New York Times article today describes leakages being many time worse than previously believed.)

- Permafrost – the frozen Arctic tundra which is rapidly thawing releases a tremendous quantity of methane.

- Hydrates (or clathrates) – a frozen slushy ice form, under the seabed is essentially pure mehane and by far the largest known quantity on the planet.

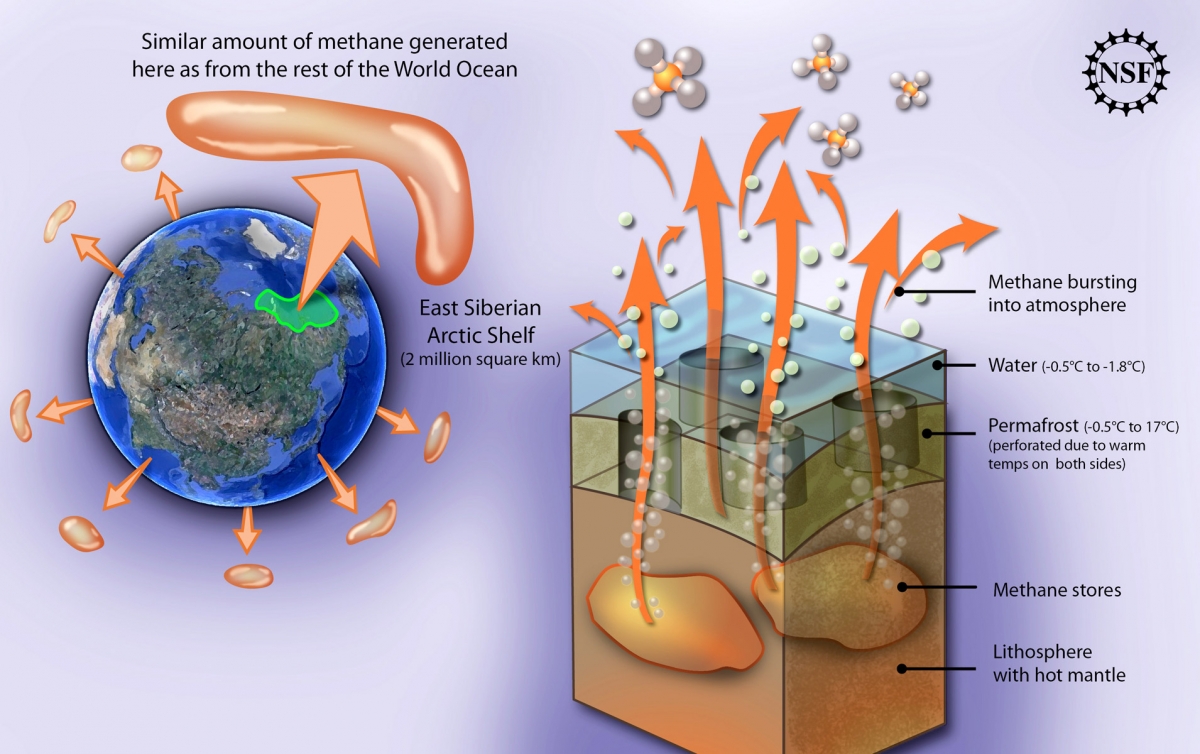

The big problem is the last two, as they are largely outside of our direct control. They are released by the Earth with as temperatures rise. The evidence is that things are starting to happen. In 2010 the National Science Foundation (NSF) published a study showing greatly accelerating release of methane in the Arctic.

The big problem is the last two, as they are largely outside of our direct control. They are released by the Earth with as temperatures rise. The evidence is that things are starting to happen. In 2010 the National Science Foundation (NSF) published a study showing greatly accelerating release of methane in the Arctic.

Several scientific ships working in the far north off Siberia reported massive areas of ocean that appeared to be like a carbonated beverage with endless tiny bubbles, which tested to be methane apparently venting from the seabed. See NSF illustration at left.

This all warrants a lot of concern and study. The possibility of a huge methane release is very ominous. Perhaps there will be some good news. In fact some new research reported today in Space Daily says that it is possible that there may be some things in a warming Arctic that actually reduce methane. But overall the methane story is really scary and should give us pause. My takeaways are:

1. We should minimize methane releases where we can directly control them such as in oil and gas operations, the subject of the EPA proposal today.

2. Research about the methane in the seabed and permafrost should continue, though it is unrealistic to expect that there will be any way for us to control those sources that are widely dispersed over millions of square miles and that are being released as a result of the thawing.

3. The prospect of massive methane release should spur us to reduce the emission of all GHG within our control as the highest possible priority. The warming is the trigger to release the other, larger quantities of frozen methane.

For those wanting more information about methane, the EPA has an excellent methane Fact Page.