Why Sea Level Projections are Misleading

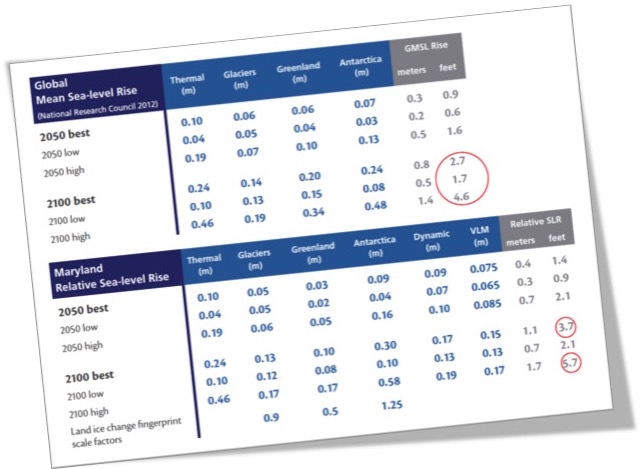

With the increased flooding at extreme high tides and awareness of accelerated melting in the polar regions, concern about sea level is rapidly rising too. Projections for the end of this century can be technical and confusing, now ranging from two feet to as much as ten feet. The page above from the State of Maryland is a good example how the scientific community and governments are attempting to make things clear and non technical. In the lower section, I have circled two of their projections: the best case projection for sea level rise by the year 2100 of 3.7 feet, and the “high” scenario of 5.7 feet.

I am not disputing their science at all. In fact, it is exemplary. This is an example of an increased effort to be clear and specific. However, despite their best intentions and good science, such explanations are actually adding to the problem. There are three aspects that concern me that are worth brief explanations:

- The focus is on the mid-range projection

- It ignores the “known unknowns”

- It suggests precision where we need to do the opposite.

Mid range projections If the estimates for rising sea level over the next eight decades are between 2.1 to 5.7 feet, it might seem reasonable to take the number in the middle. But as a metaphor would we plan for a medium hurricane? Of course not. With disaster planning, the cautious approach is to plan for the higher end of the possibilities. We have to resist the temptation to use the middle number.

Known Unknowns The overarching problem with sea level rise is that we really have no way of knowing precisely how high sea level will be 83 years from now, what we often call the “known unknowns.” There are two aspects:

First, the world is still arguing about energy policy. No one can say if we are going to burn all the coal or tar sands, use nuclear, or subsidize development of renewable energy. That choice of energy source is fundamental, as well as the exact amount of energy demand between now and the end of the century. Those two factors will determine how much warmer the planet is at that far distant point in time. Commitment to the good goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Accords are relevant, but even they were rather vague, and in no way solved the problem (Paris Climate Agreement: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly )

Second, even if we had a fairly good estimate for how much warmer the planet actually would be, we could not really quantify the precise amount of ice on Greenland and Antarctica that would melt, entering the ocean as icebergs or meltwater, both of which raise sea level. Since those two huge frozen land masses hold roughly 98% of the potential sea level rise, they are the elephants in the room. (Some may recall my post, The Elephants of Antarctica and Greenland last year.) Just to grasp the problem of accurately predicting the melting, their combined size is twice as large as the United States, and covered by ice averaging more than one mile (1.5 km) deep.

The models for the melting and collapse of the great glaciers and ice sheets are getting much better, thanks to the good field science on the ice sheets and better data from satellites and aircraft. But here’s something that hardly anyone explains. the cold, hard reality is that we will never know precisely how those massive ice sheets will melt, collapse, and slither into the sea.

To give a little insight into that, last month I attended five days of a program with 350 sea level scientists from around the world, at Columbia University. It was excellent. I learned about dozens of investigations to resolve sea level down to fractions of a millimeter––essentially a few sheets of paper in thickness. Nuances included how the ocean basins might change height by millimeters as the Earth responded to the melting ice. There was also new insight into gravitational forces. But at the end of the week, by a show of hands there was wide disagreement about whether we could get one, two, or three meters of higher sea level by the end of the century, a huge range. For non-metric Americans, that’s roughly 3, 7, or 10 feet. The models will improve, but there will always be some ambiguity about how the ice sheets will collapse even a few decades into the future.

Precision is misleading

By presenting a guideline of “3.7 feet” (1.1 meters) the strong impression is that we could know the number––the amount of sea level rise–– down to decimal point levels, roughly an inch of accuracy. As explained above we simply can not. Such precision is extremely misleading. Even the table shown has a range of future sea level from 2.1 to 5.7––and that is not the worst case scenario. It is not just Maryland, by the way. Nearly all sea level projections come up with some precise number that might be mathematically correct, but ignores the known unknowns described just above. This is precision without accuracy.

Lest anyone think that reflects badly on the science, step back and realize that we accept the “known unknowns” regarding earthquakes, avalanches, and mudslides. It is simply not possible to predict where, when or the magnitude of any of those with precision. Similarly, we plan for risks of tornadoes, nuclear disasters, terrorist attacks, deadly disease, and even financial collapse, accepting the lack of precision. We need to deal with rising sea level in a similar way.

And to be fair, if one carefully read the entire report containing the page shown at the top (Updating Maryland’s Sea Level Rise Projections), the text explains the uncertainties and gives pretty good guidance. A similar report was recently done by California by the way, that also erred in my opinion, by trying to come up with the most likely “number” for planning guidance. But the vast majority of readers do not read the “fine print”. They simply look for the highlighted number as in the table as shown above.

So what’s the answer? In fact an exemplary approach came out of the Defense Department in 2016. Their report Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for Coastal Risk Management, recognized the uncertainties in Greenland and Antarctica and recommended that future planning for sea level be done based on multiple scenarios, including some that would be considered extreme. They specifically recognized that this defied the convention to plan based on “the number.” To quote:

“The decision-making paradigm must shift from a predict-then-act approach to a scenario-based approach. As a decision-maker, the fallacy and danger of accepting a single answer to the question “What future scenario should I use to plan for sea-level change?” cannot be stressed enough. Those used to making decisions based on a “most likely” future may have trouble relating to this reality; however, a variety of uncertainties, including the uncertainties associated with human behaviors (i.e., emissions futures), limit the predictive capabilities of climate-related sciences. Therefore, although climate change is inevitable and in some instances highly directional, no single answer regarding the magnitude of future change predominates. Traditional “predict then act” approaches are inadequate to meet this challenge.”

Running multiple scenarios will give different numbers. The result is that the takeaway from studies will be to plan for a range of outcomes, likely on the order of three to six feet of higher sea level –– a meter or two. It runs against our desire to plan based on “the number.” But it is reality and when planning our future it would be wise to base it on reality.