Sea Level Rise in the Rearview Mirror

Future sea level rise will not be at all like the recent past. While there is an understandable habit or protocol to predict the future largely relying on past trends, we must overcome that tendency in this particular situation. To use a metaphor, looking in the rearview mirror is not the place to see and avoid a collision that lies directly in front of you.

Future sea level rise will not be at all like the recent past. While there is an understandable habit or protocol to predict the future largely relying on past trends, we must overcome that tendency in this particular situation. To use a metaphor, looking in the rearview mirror is not the place to see and avoid a collision that lies directly in front of you.

We are entering a new era unlike anything in the last hundred thousand years. Clarity begins with three facts: a) the ocean and atmosphere are roughly one and a half degrees F warmer than a century ago. b) according to some basic physics, the planet cannot be cooled soon, and will in fact warm further. c) on a warmer planet, there will be less ice and higher sea level.

To quote the bold findings of the Geneva Association, the insurance industry’s “think tank” in their report Warming of the Oceans and Implications for the (Re)insurance Industry: (bold face is mine for emphasis)

- There is new, robust evidence that the global oceans have warmed significantly. Given that energy from the ocean is the key driver of extreme events, ocean warming has effectively caused a shift towards a “new normal” for a number of insurance-relevant hazards. This shift is quasi irreversible— even if greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions completely stop tomorrow, oceanic temperatures will continue to rise.

- In the non-stationary [changing] environment caused by ocean warming, traditional approaches, which are solely based on analyzing historical data, increasingly fail to estimate today’s hazard probabilities. A paradigm shift from historic to predictive risk assessment methods is necessary.

- Due to the limits of predictability and scientific understanding of extreme events in a non-stationary environment, today’s likelihood of extreme events is ambiguous. As a consequence, scenario-based approaches and tail risk modeling [non-traditional statistics] become an essential part of enterprise risk management.

- In some high-risk areas, ocean warming and climate change threaten the insurability of catastrophe risk more generally.

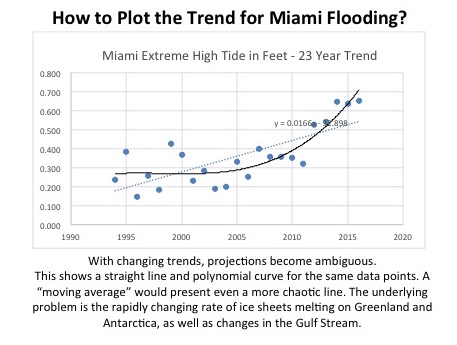

That leaves us with a tough question. If we are going to plan and adapt for higher sea level, what heights should we use? In the last few days, I happened to be on a small list of experts being polled about how to extrapolate the data for Miami, Florida – certainly an icon of vulnerability. Their challenge presents a good example of the problem, and how I explain an entirely different approach.

They are looking at recent tide gauge data, in an effort to plot the trend line, to project where thing are headed in the coming decades. Below is one of their data sets, 23 years of the high water mark from Virginia Key tide gauge (MHHW). This close up view of the data points shows how scattered they are. Applying different statistical methods yields very different directions for the future trend line, as shown here with this straight line and 3rd order polynomial. Other statistical methods would yield other curves, with even more diverse future projections. There is no “correct answer” in times of instability — what the Geneva Association called “non-stationery environments” above.

www.johnenglander.net

While we may assume there must be a good answer as to exactly how fast the water will rise, the fact is there is not. We cannot know how fast sea level will rise, because it is impossible to predict exactly how quickly Greenland and Antarctica will melt. (For explanation about why it is impossible to predict the ice melting accurately, see my blog post “The Elephants of Antarctica and Greenland.”) Not only do ice sheets, miles thick, collapse somewhat chaotically or haphazardly, we do not know how warm the world will be, which will greatly affect the melting. That depends on how the world will produce its energy in the coming decades. (Notably the debate still rages about whether we should burn all the fossil fuel as quickly as possible for short term economic benefit but we will leave that issue aside here.) The question remains as to how accurately we can predict future ice melting and sea level, based on the recent past.

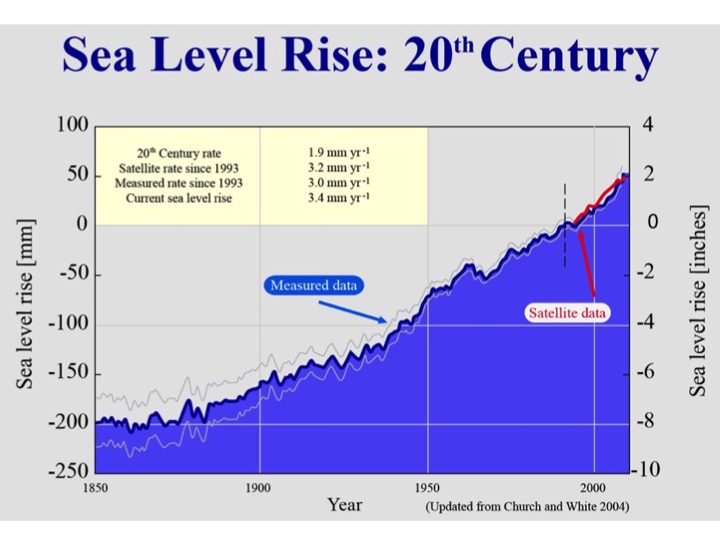

In situations of stability we can look at the recent trends to foresee the future. Plotting a trend line works well where there is a consistent force, or a smoothly accelerating one, or even a repeating sequence, or other discernible pattern. That’s not the case with higher sea level. We are entering an entirely new era, where the next few decades will almost certainly be unlike the past. Looking at the last century of global average sea level rise as shown just below, there is a broad trend of increase, but lots of inconsistencies or short term ‘blips’.

Careful examination of the red line in the upper right of the above graph shows, the trend is changing, becoming steeper showing an acceleration over the last few decades. But even this viewpoint misses the problem of precisely predicting sea level at the decade level. The lack of a clear pattern is challenging experts to “fit the curve” and therefore to know what to plan for in the coming decade or two.

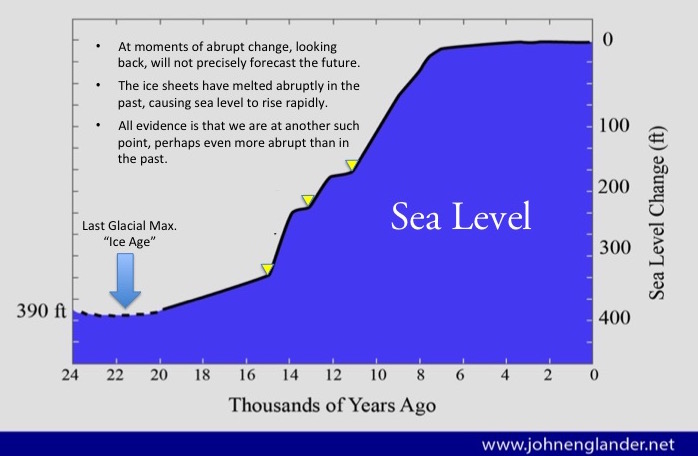

To see the problem clearly, one has to look at both the VERY detailed data such as the 23 years of tide gauge information, AND a very DISTANT view. The problem becomes clear when we look at a larger time period, several thousand years going back to the last “ice age” or glacial maximum as geologists prefer to call it. At that scale we cannot see the acceleration that is happening today, but we can see how abruptly sea level changed in the past.

As shown on the graphic of sea level change of the twenty thousand years, the rise in sea level was not smooth. There were several “bumps” or steps — sudden changes in slope of the line. If someone at any of the three points in time marked with the small yellow triangles, looked carefully at the recent past, they could not imagine what was about to occur — a dramatic increase in the rate of sea level rise. Yet, that is what has happened repeatedly in Earth history — just not in our recent five thousand years or so of recorded human history.

Obviously we must plan for the future, but need to recognize that it is impossible to do it precisely. We should take the lesson from hurricanes and earthquakes where we also can not KNOW the future – though with those phenomena, we have the advantage of hundreds of recent occurrences for better statistical extrapolation. Even with thousands of historic earthquakes to give us data points and patterns of occurrence, with vast arrays of sensors and strain gauges in earthquake prone regions, we still can not predict when, where, and exactly how strong the next earthquake will be. We plan for a relatively ‘worst case’ scenario, recognizing that we do not know exactly when or where the ‘big one’ will hit.

There is one good aspect, or consolation, with rising sea level, somewhat of a silver lining, or glass half filled. It is not possible for it to rise too quickly because we have identified some physical limitations about how quickly the glaciers in Antarctica could slide into the sea. But global sea level rise is inevitable. That combination of relative slowness, global impact and inevitability gives us the opportunity and imperative to be strategic. We can and must plan to adapt for foot after foot of rise. We must also remember that even just 6 inches of additional sea level rise can cause massive damage to fresh water supplies and water management systems in low lying areas.

The simple version of my advice to communities, national security, and corporations and homeowners is to plan for three different time horizons — short, medium, and long term, and three different scenarios — minimum, moderate and extreme, for sea level rise — which becomes a 9-box matrix. That provides a very useful tool to plan for the coming years and decades, but without trying to nail the number of inches per year. Forecasting the precise rate of rise and the consequential flooding is foolish and ignores the geo-physical reality.

In summary, I believe we are on a fool’s errand if we focus on finding the correct number of inches that sea level can rise in the decades ahead. However, knowing that the rise is unstoppable, demands that we begin planning now. Depending on the critical value and durability of the structure or infrastructure, we must make a plan for the future — what I refer to as intelligent adaptation. It is the right thing to do, both as a good investment and as a legacy for future generations. Most important, tackling new challenges gives us a sense of purpose and hope. It can inspire us.

Good perspective comes from looking at the recent past as well as the geologic past. Looking only at the recent past, can present a very distorted view.

A good metaphor is that we are driving down an icy wet road. While we should glance in the rear view mirror, it tells us nothing about the risk ahead. In fact, fixating on what is just behind us, practically guarantees a terrible collision. Better to keep our eyes on the road ahead.