Antarctic Wake Up Call – My 4 Expedition Takeaways

Antarctica is more than mysterious. It’s almost invisible to us. Last week I was back there with a group of senior corporate executives when the irony hit me. While the world is largely ignorant of and ignores that foreboding land mass as if it were irrelevant, Antarctica will dramatically change the size and shape of all the other six continents. We need to deconstruct that almost-alien world, to understand what is happening and how it will literally reconfigure our planet.

The invisible character starts with it being almost entirely monochromatic white having been frozen for some thirty million years. Also it is the least visited, most obscure, and the only continent with no legal citizens or residents. We could ignore it except that it is covered by an ice sheet a few miles thick that is starting to melt rather rapidly and will cause sea level all over the world to rise to heights never before seen by our civilization. It demands our attention as it holds about 88% of the snow and ice on the planet. Antarctica alone has the potential to raise global sea level more than 185 feet straight up.

It helps to see this enormous land mass, larger than the United States, as four distinct parts, which I can tie into my four takeaways from our exploration. Together they present a profound message that should be a wake up call.

Antarctic Peninsula “The Canary In The Coal Mine”, the appendix shaped piece that points toward South America, protrudes the farthest north, and is surrounded by ocean, which is why the warming is more advanced there. Because of its accessibility it is the most frequently visited by expedition cruise ships. Last week our group of twenty global corporate executives (on a program with SoulBuffalo Expeditions) was on a small converted Russian icebreaker. We visited two of the research stations, Palmer (US) and Vernadsky (Ukraine) in this region.

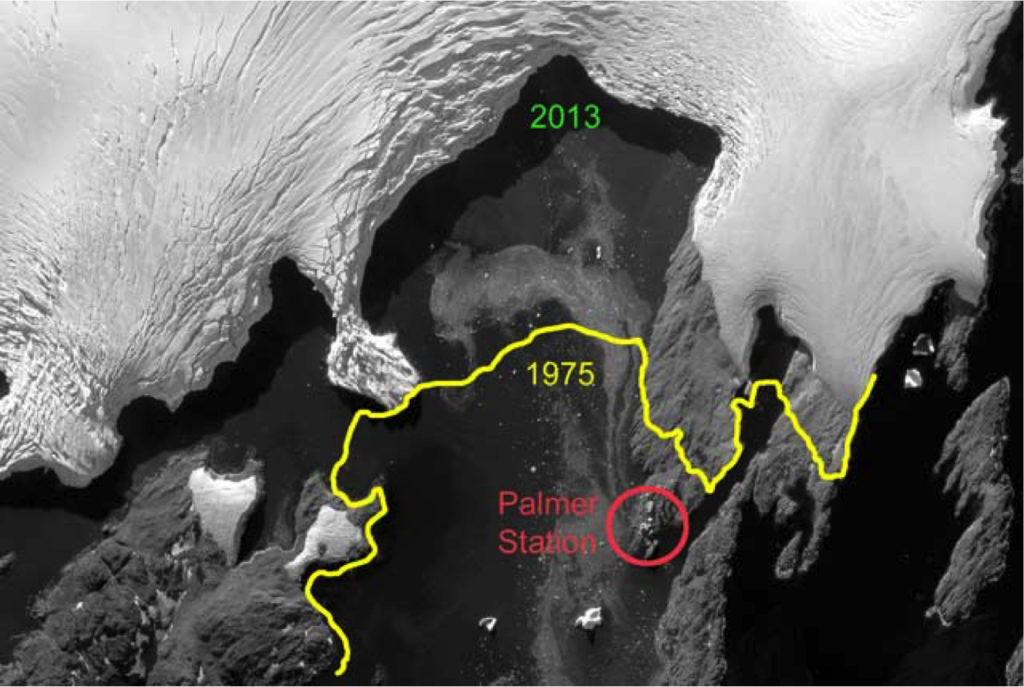

Key Takeaway #1: The evidence of warming and melting is very apparent compared to my visit to the same locations a decade ago. “Glacial speed” used to mean extremely slow. Not any more. We are now in a new era of accelerating melt that shows no signs of letting up. Think of the changes to this peninsula as the “canary in the coal mine.” As shown on this aerial image below of Palmer Station at Marr Glacier, the ice is receding quickly.

East Antartica “The Elephant In The Room”, comprises about two thirds of the total area and is the most stable part of the continent. There is enough ice on East Antarctica to raise global sea level by almost 170 feet (50 meters). That will not fully happen for many centuries, but there is a more imminent problem. While some parts of East Antarctica send confusing signals with more snowfall, we now have good measurements about key areas that are destabilizing.

Key Takeaway #2: Size does matter — just 3% of East Antarctica melting will raise global sea level by more than five feet — enough to swamp nearly every coastal area in the world. More and more studies agree on the increasing possibility of such a scenario this century.

West Antartica “The Tipping Point”, roughly a third of the surface area, is a combination of mountains and underwater valleys all covered by snow and glaciers. Though its appearance is similar to East Antarctica it is much less stable. In particular the six Pine Island glaciers are the focus for vulnerability. Since 1978 the major concern has been that these glaciers are poised to collapse and slide into the sea, potentially raising global sea level up to ten feet (three meters). The latest data indicates that this could start to occur in the next 3 to 4 decades. Most experts agree that this region has already passed the point of no return. It is no longer a question of “if” but rather how soon will it collapse. That instability is what has brought us to the tipping point.

Key Takeaway #3: All bets are off. The fact that the recent past, no longer predicts the future presents a huge challenge for almost all aspects of society from community resiliency to business continuity to mass migrations and national security. The next 40 years will be nothing like the last 40 years. (See Post “Elephants of Antarctica and Greenland” for more.)

The ice shelves “The Cork In The Bottle” — including Larson, Ross, Pine Island — are huge areas of ice, more than five hundred feet thick that fill the large bays. Like icebergs or even ice cubes in a glass, the melting of ice shelves does not directly affect the level of the liquid because it is floating ice. But the large ice shelves act like giant plugs holding back the glaciers on land. As these ice shelves crack and disintegrate it allows the glaciers on the land to slide into the sea, which is what will cause sea level to rise. Larson C has been in the news recently with an area larger than Delaware poised to break free. Our trip last week planned to visit Larson C, but there was so much ice piled up and floating in the area that it was unsafe for our ship.

Key Takeaway #4: The plug is being pulled. The continued breakup of the ice shelves, like Larsen C should be sounding the alarm that the glaciers will then be able to move more quickly, raising global sea level much faster than in the recent past. (See Post “Sea Level Rise in the Rear View Mirror”)

Antarctica will not operate on our timetable or pay the least attention to our political dialogue or minimal action. What happens there will not stay there. It occurs to me that though few will ever visit this mysterious distant continent, its ice sheets will melt and then “visit” us where we live — in every coastal city of the world.

From this latest expedition it is clearer to me now more than ever that we must heed the wake up call from Antarctica. While we do have time to plan and adapt, we would be well advised to think bigger and act sooner. We really have no time to waste.